The scientist was on the front lines of the biotechnology that has rewritten the trajectory of agriculture and its global potential.

Modern agriculture and the path toward global food security would look radically different without the pioneering efforts of Dr. Robb Fraley. The scientist, who would go on to become chief technology officer at Monsanto, saw the company through a dynamic period of innovation, investment, and restructuring that earned him numerous prestigious awards.

“We knew it was important,” said Fraley, who retired from Monsanto in 2018 when the agricultural company was acquired by Bayer. “It’s so exciting to see today how far this technology has developed, and really, it’s still very nascent in terms of the potential that we see going forward. There’s a lot of opportunity for new biotechnology traits where you’re introducing a new gene that gives a crop plant a new property.”

From his elk hunting cabin in Colorado, where Fraley goes to relax, take in some recreation, and spend time with his sons and grandkids, the 71-year-old former executive spoke at length about his lifelong interest in learning, his early days at Monsanto, the way genetic engineering has improved the farm landscape, and what he sees as the next stage for biotechnology.

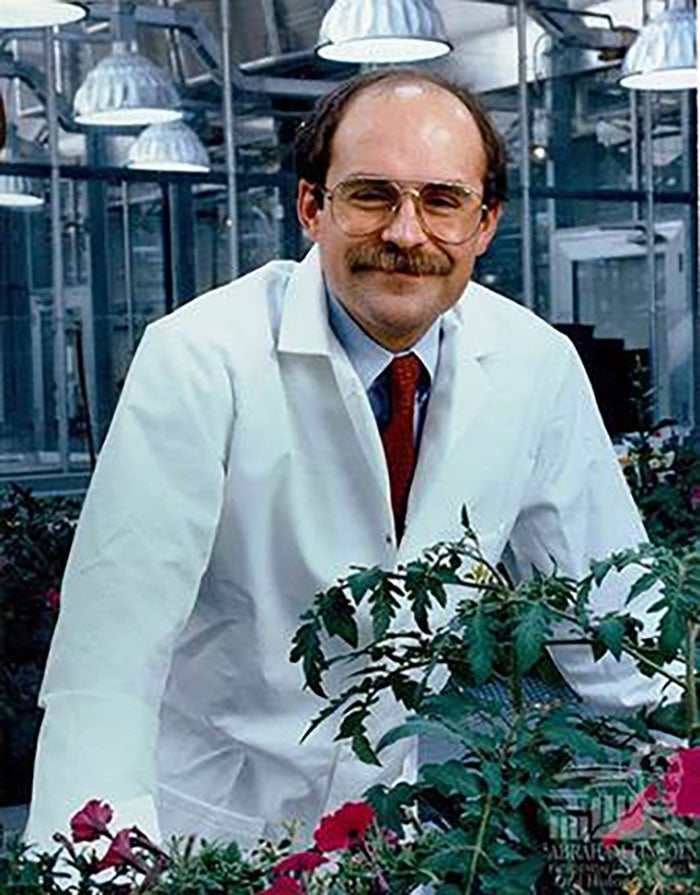

Robb Fraley grew up on a family farm in Illinois. (Image courtesy of the World Food Prize Foundation)

Raised on a farm near Hoopeston in central Illinois, Fraley says he always knew he was going to become a scientist — his childhood reading would include encyclopedias, and he’d often busy himself drawing pictures and diagrams.

When the opportunity for college came, he attended the University of Illinois, working through several career options across medicine and veterinary science. He stayed at U of I for graduate school to study microbiology, which exposed him to many of the technologies that were being developed throughout the 1970s.

“I think that’s when my farm background and rural interest kind of connected,” Fraley said. “After I left Illinois, I did a postdoc out in San Francisco — at UCSF, which was kind of where the biotech world started.”

Beginning in the mid-1960s, the University of California, San Francisco, positioned itself as the epicenter of a revolution in the health sciences and the creation of the biotechnology industry. Biotech was rapidly advancing how medical research was being conducted, and it wasn’t long before an overwhelming majority of new pharmaceutical products were produced through biotech means.

In 1973, university researchers Herb Boyer and Stan Cohen invented recombinant DNA technology, giving them the ability to introduce a gene from one bacterium to the next. Around the time Fraley was doing his postdoc, their work led to the founding of Genentech and the cloning of the gene for insulin. Similarly, the biochemical structure for growth hormones was identified and replicated in the late ’70s.

This science was progressing at an impressive pace, and Fraley recognized how this could apply to agriculture.

When he began looking for jobs in 1980, The Monsanto Co. — which was an industrial chemical manufacturer primarily focused on plastics and crop chemicals — stood out as a company that both had the resources and the vision to see the opportunity to elevate the agricultural sector through biotechnology.

“Like for a lot of people, the path only looks predictable when you look at it backward,” Fraley said. “But I think that ended up being a pretty good choice.”

When Fraley was hired, Monsanto had made some early investments in Genentech and other biotech startups, and the company was concerned that the future of the chemical world might begin to change more drastically. Glyphosate was still relatively new to the market, and the technology wasn’t there to be able to apply it to crops … yet.

Fraley, with his background in gene delivery, was one of three principal scientists on his team at Monsanto — the others were Rob Horsch, who was a tissue culture expert, which was key to being able to regenerate cells that eventually were transformed, and Steve Rogers, a gene-cloning expert.

“It was really a pretty small team for several years,” Fraley explained. “Everything clicked, and we were able to, in just a few short years in ’83 and ’84, demonstrate the ability to put a new gene into a plant cell to give it a new property. And that really opened the door for eventually working on glyphosate resistance and creating Roundup Ready, as well as the Bt technology to create YieldGard and Bollgard cotton.”

Dr. Robb Fraley spent decades as a scientist and biotech leader at Monsanto. (Courtesy image)

Dr. Robb Fraley spent decades as a scientist and biotech leader at Monsanto. (Courtesy image)

What stands out is that this was a prolonged and unprecedented investment that Monsanto was making. While the technology was discovered in the early 1980s, the first commercialized products were still more than a decade away, forced to wade through an evolving federal regulatory system that demanded a new level of cooperation between three key agencies: the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Department of Agriculture, and Food and Drug Administration.

The regulatory work and the health and environmental testing that was done led to “lots of exciting science and lots of challenges to overcome during that period,” Fraley said.

That small team at Monsanto saw it was onto something big, but the recognition of just how big might be lost to the generations.

“It was clearly possible that this technology would have a dramatic impact on agriculture,” he said, noting how there were two major fronts that impacted crop yield each year. “We focused on agriculture’s biggest challenges: how to control weeds in a farmer’s field and how to control insects. We were working on glyphosate tolerance. Roundup was a terrific product that controlled a vast majority of the farmers’ weeds. So, if we could make crops like soybean or corn resistant to Roundup, we knew it would be a big deal.

“I’m not sure though that we believed that it would have the kind of impact that we’ve seen with it across multiple crops and multiple countries,” he said.

Dr. Robb Fraley is shown working in Brazil. (Image courtesy of the World Food Prize Foundation)

Dr. Robb Fraley is shown working in Brazil. (Image courtesy of the World Food Prize Foundation)

Glyphosate, a non-selective herbicide that stops a specific biosynthetic pathway, was created by Monsanto and went on to become the most widely used synthetic crop protection product in the world. That was due to both its effectiveness as a weedkiller and the glyphosate-resistant Roundup Ready corn and soybean seeds that Fraley and his colleagues were able to create.

“It took a combination of both interest in moving into something different and in having the resources and commitment and vision to do it,” Fraley said. I give the leadership of the company a lot of credit for steering the company in this direction.”

While biotechnology alone doesn’t guarantee strong crop yields (weather, timing, and soil health are just a few of the other factors), it’s no accident that the more biotechnology can progress, the better yields become. And for 2024, predicted corn and soybean yields per acre in the U.S. are at record highs.

Since Fraley’s early years at Monsanto, there have been notable advances in disease and climate resistance in plants, and the development of gene-editing technology, which can speed the path through the regulatory system, has helped countless farmers.

“Robb was the best boss I ever had,” said Jan Street, executive assistant at Bayer who worked closely with Fraley while they were at Monsanto. “He was thoughtful, wickedly smart, and always did what he thought was best for the customer and the company. He encouraged us to ‘take the shot,’ putting customers first and always had their back.”

Monsanto’s leadership set the stage for where agriculture biotech is today through two pivotal steps.

First, Monsanto gave others a stake in the success of biotech by licensing the technology broadly to competing companies, a wildly foreign concept at the time. The licensing and subsequent royalty money provided Monsanto with a high-margin revenue stream and eased some of the burden of the long-tail investments it had been leaning on.

“It created a common bond, even among competitors, to help drive the success of the technology,” Fraley explained. “And we avoided the ‘haves’ and ‘have nots’ in the industry, giving all the players a stake in the game to help bring these new products to the marketplace.”

Dr. Robb Fraley speaks at an Iowa research facility in 2006. (Image courtesy of Chuck Zimmerman, ZimmComm)

Dr. Robb Fraley speaks at an Iowa research facility in 2006. (Image courtesy of Chuck Zimmerman, ZimmComm)

Monsanto also began to buy up seed companies to deliver the technology more quickly and directly to farmers. This created a sense of momentum with biotech and positioned Monsanto on the front lines of this industry, even if the acquisition of seed companies was an unplanned expense.

“We were starting to appreciate that a lot of the new biotech tools were going to directly have an impact on breeding crops better and faster and more efficiently,” he said, “so there was an economic benefit of using this technology within our own seed and breeding companies.”

This was so successful that a transformation took place, and a “new Monsanto” was launched as a public company in 2000. It raised $700 million in its initial public offering, a strong number even if slightly below the internal expectations.

Economic analysts posited that the lower-than-expected IPO price was due to something that dogged Monsanto for decades: the public’s acceptance of genetically engineered crops.

“We underestimated, like a lot of companies did, the power of the then-developing Internet to create communication and networks of opposition,” Fraley noted. “And it was clear that some of the responses were negative. I don’t think we were as prepared as we could or should have been to address that both as a company and as an industry.”

Today, he said, the company — and the agricultural biotech industry as a whole — are doing a better job of making the benefits of genetic engineering understood by the public and that issues and concerns are being addressed.

“I worked with Robb at Monsanto when his role had expanded to public outreach on topics like GMOs and pesticides,” said Vance Crowe, Monsanto’s former Director of Millennial Engagement and current host of The Vance Crowe Podcast. “At the time, he was learning to temper his directness, because the trait that enabled him to harness the best in his scientific staff didn’t connect with regular people. But Robb studied communication with the same intensity that he brought to science and quickly became a highly sought after speaker, someone people trusted after they heard him.

Now, nearly 30 years after the launch of the first genetically engineered food products, there is a broader acceptance of biotech in the United States. Research has shown that Generation Z is far more inclined (77 percent) to accept food made through technology than previous generations were (58 to 67 percent). In line with that, Gen Z is routinely viewed as the “greenest” generation yet.

According to the international nonprofit ISAAA, nearly four dozen nations, along with the European Union, cultivate at least one GMO product.

In the United States, 13 genetically engineered crops have been approved for farmers to grow. According to the USDA’s Acreage report, the nation planted biotech varieties on 93 percent of corn acres, 97 percent of soybean acres, and 95 percent of cotton acres.

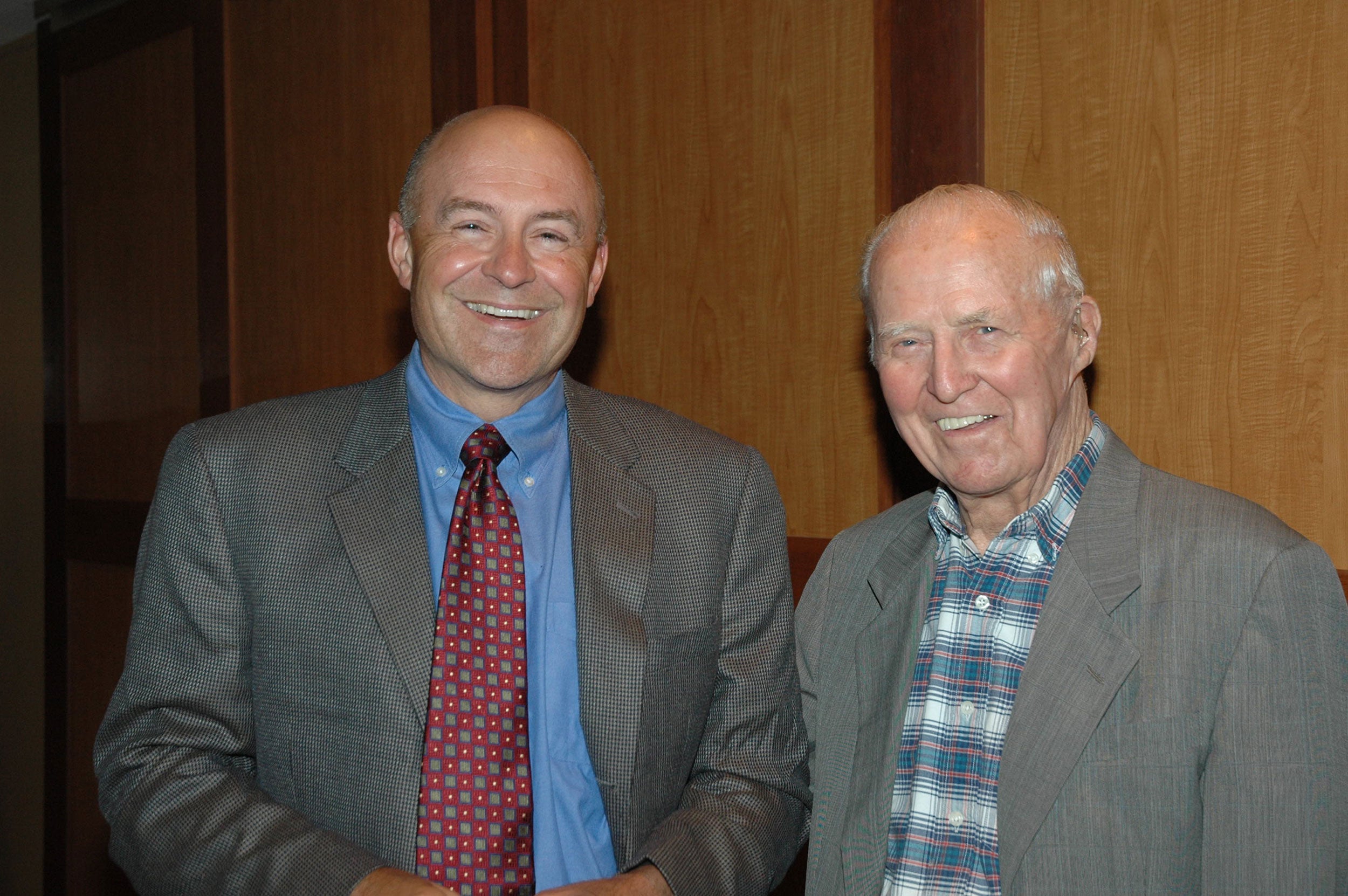

Drs. Robb Fraley (left) and Norman Borlaug are two of the most influential agricultural scientists of the past century. (Image courtesy of the World Food Prize Foundation)

Drs. Robb Fraley (left) and Norman Borlaug are two of the most influential agricultural scientists of the past century. (Image courtesy of the World Food Prize Foundation)

Like most biotech scientists, Fraley believes that genetic engineering can fit into what’s commonly referred to as “regenerative agriculture” — the type of farming that looks toward soil health and finds harmony amid the environmental and economic impacts of production.

“If you think about the driving mantra of producing ‘more with less input,’ that’s a real win for everybody, from both a food security and from an environmental perspective,” Fraley said. “That’s whether we’re talking about biotech traits like the weed control traits that allow farmers to use less herbicides and get better protection of their crop from weeds, or the insect and disease traits that allow for substitution of chemistry or creating other benefits.

“Gene editing and advanced breeding techniques can play a pivotal role in developing better-adopted varieties and hybrids for the future,” he added. “And that’s a win across all types of agricultural production, whether it’s organic, whether it’s regenerative, or whether it’s in commodity production.”

In recent years, Fraley has listened to his own advice and has taken time to himself since retiring. He was in the room when Bayer made its offer to buy Monsanto, something he noted was a bit shocking at the time because Monsanto always considered itself the acquirer and not the acquiree.

But Bayer’s expertise in chemistry and Monsanto’s pioneering biotech made for a complementary product portfolio and helped move the $63 billion merger to fruition in 2018.

However, in the years since, tens of thousands of people have sued Bayer over the glyphosate-related products it acquired from Monsanto. Early court proceedings resulted in billions of dollars’ worth of legal rulings that have squashed much of Bayer’s financial might, though there are signs of a shifting tide, as recent court rulings have gone in the company’s favor.

Monsanto (and subsequently Bayer) also became a popular target for environmental activist campaigns and the subject of news articles and books, many of which were unfavorable toward the company. But growers themselves overwhelmingly embraced the technology that came out of Monsanto, which allowed them less aggressive crop protection mixes, the ability to more easily have no-till operations, and to better cope with scaling up farmland acreage despite labor shortages in the industry.

“I think that this technology is starting to hit full stride in terms of its applicability to everything from disease and insect and the agronomic traits, but also to stress and yield traits that I think are going to be very important for the future,” Fraley said.

Dr. Robb Fraley takes part in a panel discussion titled, Innovation, Biotechnology, and Big Data, at the 2015 Agricultural Outlook Forum. (Image courtesy of Lance Cheung via the USDA)

Dr. Robb Fraley takes part in a panel discussion titled, Innovation, Biotechnology, and Big Data, at the 2015 Agricultural Outlook Forum. (Image courtesy of Lance Cheung via the USDA)

Fraley has spent a career advocating for this kind of innovation and advancement in agriculture. Ben Eberle, Senior Communications Manager for Bayer Crop Science’s Digital Farming Platforms, first worked with Fraley during the 2016 unveiling of 39 North, an agtech innovation district in St. Louis that Bayer continues to support to this day.

“What also stood out to me about Dr. Fraley was his willingness and versatility to communicate on a number of topics,” Eberle said. “On Monday, he might be in a broadcasted debate about modern agriculture, on Tuesday he’s hosting a global townhall with thousands of employees, later that afternoon he’s welcoming a camera crew to his home and talking about home gardening. Telling the story of farmers, agronomy, and ag technology was something he took very seriously.”

The former executive spent a year consulting with Bayer before stepping away completely in 2019, and today he sits on the boards of several small technology companies.

He said these days he enjoys pursuing several outdoor activities, including skiing, gardening, and hunting while following the industry trends and giving talks periodically.

Fraley has a lot to look back on fondly.

He remembers the excitement of his colleague, the tissue expert Horsch, running down the hallway with Petri dishes in hand, showing that Monsanto’s new genes were growing green shoots in the presence of an inhibitor.

He also remembers driving down rural roads in the late 1990s, quickly identifying soybean fields that were using the Roundup Ready seeds he helped create.

“Over the years, I would have farmers — and often sometimes a whole farm family — come up to me at a talk and say, ‘This technology has really changed my farm,’ and that they liked being able to grow a crop with reduced chemicals or one advantage or another. That was really impactful,” Fraley said.

And still, the biotech world is moving forward rapidly, where the ability to do an analysis of plant genes and to sequence all the genes in corn, soybeans, and literally every crop that’s planted around the world, allows breeders to make better decisions and pick the rare seed or rare individual plant that has the desired traits from both parents.

It seems likely that this industry will have more pioneers like Fraley.

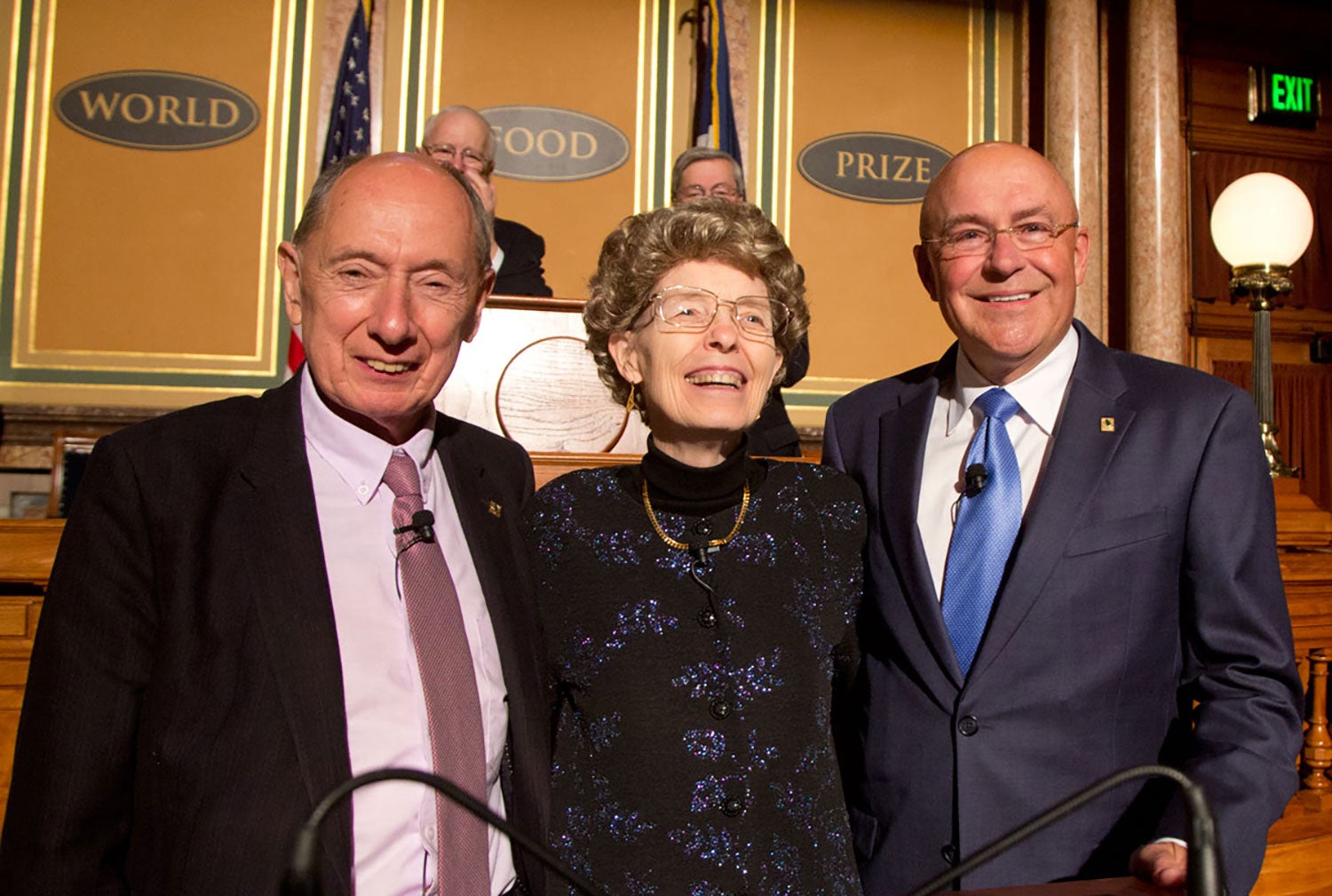

The 2013 World Food Prize Laureates were Dr. Marc Van Montagu, Dr. Mary-Dell Chilton, and Dr. Robert T. Fraley (Image courtesy of the World Food Prize Foundation)

The 2013 World Food Prize Laureates were Dr. Marc Van Montagu, Dr. Mary-Dell Chilton, and Dr. Robert T. Fraley (Image courtesy of the World Food Prize Foundation)

Fraley was awarded the National Medal of Technology by President Bill Clinton in 1999, shared the 2013 World Food Prize with Drs. Marc Van Montagu and Mary-Dell Chilton for their development and application of biotech in the ag space, and was welcomed into the Order of Lincoln, a prestigious honor given by the state of Illinois. He also recently received the Farm Foundation Transformational Leadership Award.

That last two awards, he said, are “particularly warm and meaningful because they are from people who know you personally — from customers or business associates who’ve you’ve worked with. Yet it’s also a bit awkward. The recognition is wonderful, but it really took a team of people and a vision from the company leadership to achieve this.”

He appreciates the “people part” more than anything, and he believes that that is a major part of what will help propel the application of biotechnology for future growers.

“The powerful combination of having a great science and great people can overcome most challenges,” Fraley said. “And that’s true both in agriculture and in every other facet of life.”

Ryan Tipps is the founder and managing editor of AGDAILY. He has covered farming since 2011, and his writing has been honored by state- and national-level agricultural organizations.

Sponsored Content on AGDaily

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source link