The Perth Entertainment Centre, January 13, 1995. The first moments of the first night of the world tour. When the arena lights flicked off, a vast roar filled the blackness. Eight thousand Australians standing up and going waaaaaaaahhhh! The moment lingered and expanded on itself. So much at hand, so much at stake. Onstage, they could feel a solid wall of noise coming at them, the power humming in the amps. The musicians slipped into their places, instruments in hand, the electricity in their fingertips.

This moment they’d first anticipated in the spring of 1993, that they’d hoped for and dreaded, that they’d dreamed of, that they’d argued about, that they’d been planning and preparing for, was right here, right now. Peter Buck, his left hand holding the neck of his guitar, took a breath, then raked a pick over the strings, sending a loud buzzing chord into the air. Then another chord, tripping a blast of drums and a bolt of clear light revealing five musicians and R.E.M.’s lead singer, Michael Stipe, shouting a single word into his microphone.

WHAT!

The drums and bass hit and then they all shot off together.

“What’s the frequency, Kenneth?” is your Benzedrine, uh-huh / I was brain-dead, locked out, numb, not up to speed…

And there it all was. The present and the past, the signal and the noise, the insiders and the outsiders, the melody and the dissonance, all of it rolled into sound and beamed upward until it exploded, the fractured light of a mirror ball.

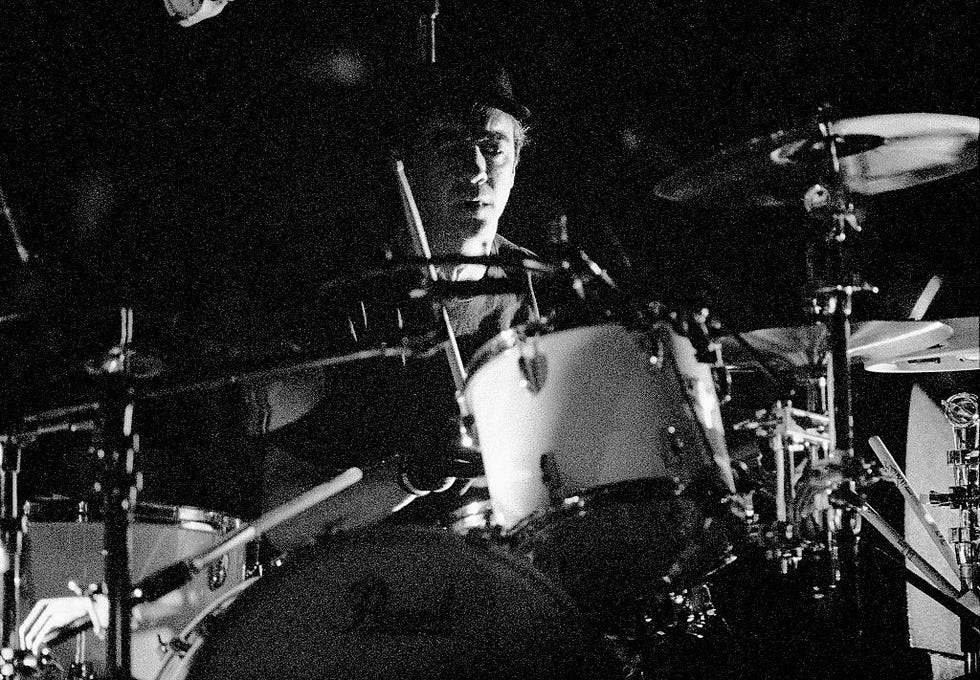

This was the part Bill Berry lived for, the moment when the lights went out and the music took over. He’d started talking about going back on the road in 1992. “We miss touring,” the drummer told a reporter from Europe’s Super Channel in October 1992. That was in the wake of R.E.M.’s multi-platinum album Automatic for the People, when he realized he was tired of all the mid-tempo songs that had no need for a drummer pounding away. Bill had helped write a bunch of those songs, but still. Enough was enough: the band’s performance chops had dulled, the time had come to rock.

When he was interviewed by MTV as it was all coming together two years later, you could see a gleam in the drummer’s eye. “It’d just kinda be fun to go out and be a kid again,” he told one of the throng of interviewers witnessed by the cameras of Rough Cut. “I’ve got new drums and I get to hit ’em real hard. Pete’s got a new amp and he gets to turn it up all the way. We get to be kids again.”

But there was performing, the part that made him feel like a kid, and then there was touring, which made him, at thirty-six years old, feel like an old man: exhausted, disoriented, aching for home. The irony was in how hard, and how long, Bill had worked to get himself and his band to this position. If anything, they’d overshot the goal: he’d wanted to make music that was popular enough to earn them a living, but they’d become so big that the demands of popularity were drowning out the music.

Bill and his bandmates had set out to become something more than rock musicians. They wanted to be rock stars.

And still the music kept calling to him. Particularly the kind they could only make playing live, in front of an audience. The energy, the sound, the heartbeat rhythm connecting him to his three bandmates and to the thousands of people breathing and shouting and moving along with them. “As much as I hated a lot of the parts of being on the road and away from home, I was ready to go,” he said. “Five years off—it was time to do it.”

And not in some half-assed way, either. When Peter proposed making the 1995 tour a small-scale enterprise, a return to the clubs they’d played back in their earliest days, Bill put his foot down. “Fuck that. I’m not going backwards.” This was where the drummer seemed to be at odds with himself. Even as the new tour was coming together, he spoke of how he’d loved the club years the most, when they could play whatever they wanted, for as long as they wanted to, without worrying about the rules and regulations that had first landed on them when they stepped up into theaters. “Going onstage exactly at 9:20 and making sure you got off at 11:15 or you were going to be fined,” he told Gerrie Lim, writing for BigO in the fall of 1994. “Those kinds of strictures made touring a lot less fun. And it was kind of ironic, because the more money we made the less power we had over what was going on.”

The Name of This Band Is R.E.M.: A Biography

But like most, or maybe all, aspiring rockers, Bill and his bandmates had set out to become something more than rock musicians. They wanted to be rock stars. And what the rock stars of the 1990s did, along with selling millions of records and ascending to the upper altitudes of celebrity, was tour the world, playing the biggest arenas, stadiums, and festivals they could play. And as Bill gleefully told MTV, that’s what R.E.M. was going to do, starting in Australia in mid-January. “Friday the thirteenth,” he said, elevating his impressive brows. “That’s for good luck.”

The touring party gathered in Perth at the end of the first week of January, set up the stage in the Perth Entertainment Centre, where the tour would open, and spent a few days in full rehearsals, working the final kinks out of the set, making certain the light and film cues were in line and girding for the coming rigors. When they finished work on January 12, the entire touring party was invited to the Cottesloe Civic Centre, a converted estate near the sea, to attend the wedding of Peter and Stephanie Dorgan. A reception followed, with music provided by tour openers Grant Lee Buffalo. Later, when a reporter mused about how he’d sacrificed a honeymoon with his bride by getting married the day before the start of a world tour, Peter chuckled. “I get to play guitar and travel all over the world,” he said. “That sounds pretty much ideal to me.”

They fiddled with the set list over the next few weeks, moving “Kenneth” into the encores, then putting it back at the start of the set, shifting one or another old favorite (say, “Begin the Begin” or “Disturbance at the Heron House”) into the first suite of songs, then shuffling the deck again. Eventually they settled on opening with three and sometimes four straight Monster songs, the better to establish that they were a modern band working in the moment, not milking their past to connect with the audience.

They had all grown and changed in visible ways. Bassist Mike Mills, thirty-six years old and spangled from his ankles to his neck and out to his wrists, hair long and silken, had traded his approachable nerd look for full-on glam rock. Peter, thirty-eight and now a father of two, prowled his side of the stage like a field general, dressed in plain pants and a lightly ruffled tuxedo shirt, limiting his spins and jumps, his mind firmly on the music. Often he drifted back to lock in with Bill, who marshaled the beat with no-nonsense authority, dressed in plain trousers and a T-shirt.

Jeff Kravitz//Getty Images

Jeff Kravitz//Getty Images

R.E.M. at the MTV Video Music Awards in September 1995.

But it was Michael, now thirty-five, who embodied the spirit of Monster and the tour. Radiant with a kind of ironic audacity, he’d take the stage in aluminum-framed sunglasses, a T-shirt, and jeans, a wool hat pulled low over his eyes, then greet the crowd with a tetchy WHAT!, as if summoned by an unwanted knock on his front door. Then Peter would kick things off with the opening of “Kenneth” or “I Don’t Sleep, I Dream” or “I Took Your Name,” any of which might start the show, and when the song took him, Michael moved like a snake on legs, bending forward and backward, dancing with the microphone stand, batting it around, lurching this way and that.

When he addressed the crowd, he teased and flirted in the same breath. “I went down to the beach the other day. Did anybody down there see me?” he said one night in Australia. When someone shouted back, he looked down carefully, then nodded. “Oh, hi, I remember you.” He pointed to the music stand next to his mic stand. “You may have noticed that I’ve been reading the lyrics off of a sheet of paper.” A shout. “Why? That’s a stupid question.” He laughed and then barked with mock authority. “Take off your clothes and lick the floor.” A beat. “I was kidding!” Everything he said came through a crooked smile. “Well, that was a song,” he’d announce. “Now we’re going to play another song. After that we’ll play another song, and then another one after that. And it’s going to go on like that for a while.”

They picked up speed and took to the air, the ground blurring with their velocity. January in Australia, one show in New Zealand, then off to Asia at the start of February. A pair of shows at the Budokan, in Tokyo, then one-show-and-go visits to Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Singapore before the entire enterprise made the long flight across the planet to Spain. They got a few days to rest before the European tour began in San Sebastian on February 15. That trip, more than twenty-four hours from hotel-room door to hotel-room door, inspired the writing of “Departure,” a full-speed-ahead guitar blast that was the first of the newly written songs to make it into the show. The song’s first line—Just arrived Singapore, San Sebastian, Spain, twenty-six-hour trip—was a literal description of the band’s recent journey across the planet. There’s so much to tell you, so little time / I’ve come a long way since, uh, whatever…

Paul Natkin//Getty Images

Paul Natkin//Getty Images

R.E.M., left to right, Bill Berry, Michael Stipe, Mike Mills, and Peter Buck, photographed at the Aragon Ballroom in Chicago, Illinois, July 7, 1984.

During the 1980s, touring had been R.E.M.’s way of being. They’d traveled all over the world, by car, van, bus, train, boat, and airplane, had performed in venues large, small, and midsize, had faced audiences that ignored them and audiences that sang along with every syllable. But they had never toured as international celebrities, and what soon became clear was that this made for what Peter called a “weirdly unpleasant” experience.

Previously, whenever they’d found crowds waiting outside a hotel, they’d assumed someone far more famous than they were was also staying there. This time around, the crowds were looking for them. “Your phones would be ringing at weird hours, people would camp in the hallways,” Peter told the British journalist Tony Fletcher. “It was so fucked up and chaotic I quit drinking. I stopped drinking in February and didn’t have another drink until the end of November. I was just like, this is too insane. I have to be sober for this whole thing to keep it together.”

Peter also had his new wife and their twin baby girls to keep him grounded. The other band members did their best to keep their inner circle insulated from the weirdness triggered by their fame, and from the more toxic habits and rituals of the rock ‘n’ roll road. They revised their standard performance contract to limit the backstage beverage options to soft drinks, beer, and wine, no more bottles of vodka, scotch, and gin, thanks very much, and to make sure the buffets had plenty of vegetables and other healthy options for band and crew alike. They brought a treadmill for Peter and Bill to exercise on, while Michael combined his exercise with sightseeing, pulling a hat down over his head so he could explore his whereabouts on foot without drawing attention. Bill and Bertis Downs brought their golf clubs, and if there was a course anywhere nearby, they’d take off together to get in nine holes before soundcheck.

After the shows, the band members and their wives or romantic partners often got together in the hotel bar or in someone’s room to unwind together with party games—charades or a board game, Pictionary and Trivial Pursuit usually. “It wasn’t rock-star-like,” Bill’s ex-wife, Mari, recalls. “Not a lot of partying. It was family-like, very quiet. People got really obsessed with the games.”

The pressure continued to build. The crowds, the lights, the cameras. Monster had sold two million copies in the United States alone within two months, and it was still selling, pushed along by the single releases of “Bang and Blame” and “Crush with Eyeliner,” both of which scaled the various Billboard charts on the strength of heavy airplay all across mainstream rock and alternative radio outlets. Sales and airplay were just as strong in Europe, and the media coverage fed excitement when the band came to perform, which fed the crowds and the mood of mayhem that seemed to blow up wherever they went.

Weird things started to happen. At the first of two shows in Rome’s PalaEUR sports arena on February 22, the band was still in the opening verse of the set-opening “What’s the Frequency, Kenneth?” when the entire place lost power. A loud bang! and then blackness, a brief echoing silence, and then a big cheer—was it part of the show? Well, no. The lights came back on after a minute or two, the sound system came back a moment later. Bill slapped his sticks together and they picked it up pretty much where they’d left off, rock ‘n’ roll business as usual. For fifty-five minutes anyway, until the end of the first verse of “Man on the Moon,” when it happened again. Bang!, then blackness. When the lights blinked back on, Michael stood at the center of the stage, shaking his head at the crowd. “What the fuck is going on here?” he said, sounding truly puzzled. “Does this happen all the time? Did somebody put a curse on us or something? I didn’t think so.”

Then they got back to it, taking “Man on the Moon” from the top (“It’s one of the highlights of the show,” Michael explained), then into the main set’s emotional climax (“…Moon” into the slow boil of “Country Feedback” into the outburst of “Losing My Religion”). A few more songs would fill in the main set, and there’d be a brief pause before the encore began with the bloody, mournful “Let Me In,” which gave way to the soothing “Everybody Hurts.” After that would come a few show-ending rousers and the new single, “Bang and Blame,” before they finished with a riotous rendition of the beloved-hit-that-wasn’t-actually-a-hit, “It’s the End of the World as We Know It.” The last note would still be echoing around the darkened hall, competing with the crowd’s cheers, when the first of the band’s buses would roar away from the venue. Inside would sit the band’s ambivalent drummer, ears still ringing, spirit keening to be somewhere, anywhere away from the noise, the crowds, and tumult.

They had a day off before the show in Lausanne. A six-hour journey from Bologna after the February 27 show, then a long, quiet day in a Swiss hotel to catch up on sleep in a real bed, get up whenever, maybe take a walk and explore, visit a park, or do a little shopping and go out for a meal or two before the 2 p.m. call for soundcheck at the Patinoire de Malley arena for the March 1 show. Grant Lee Buffalo was opening on this part of the tour, so they went first, playing for five or ten minutes while the crew got their balances right in the amps and PA. Then R.E.M. and their two supporting musicians came moseying out, the instrumentalists first, jamming a song or two before they’d go over something in the set that had thrown them at the last show, or get going on something new.

Six weeks into the tour, the workdays ran more or less like clockwork; everyone had their pre-show rituals, the anticipation building when the doors opened and the place thrummed with voices, feet, the happy buzz of concertgoers gearing up for their evening with the hottest band of the season.

WHAT!

Onstage in Lausanne. The explosion of light and sound, the cheers and applause coming at you like a wave, a physical thing strong enough to knock you off your feet. This was where Bill could hit his drums hard enough to keep the noise and chaos at bay, where his beat kept everything orderly, moving at his pace. After fifteen years together, and now nearly two months into the tour, the performances were built on a combination of physical energy, emotional projection, and muscle memory. Michael’s job was a little different, channeling so much feeling into the words he sang, his focus divided between singing, moving, and monitoring the crowd while also listening to the band. Behind him, Bill focused almost exclusively on the music, keeping his beat straight and strong, adding harmonies when his parts came up.

Then they were off, into the opening suite of Monster songs, then a pair from Out of Time, “Me in Honey,” “Half a World Away,” usually with one or two from Automatic. It was always great to hear the ovation the songs from the previous few albums got when they started playing them; nobody complained about not hearing “Radio Free Europe” or “So. Central Rain” or any of the early ones they’d put away. “Man on the Moon” was always a highlight: the music had such a nice groove, and Michael had taken to emphasizing the whole Elvis aspect, he’d be all slinky hips and sexy Memphis drawl for the Heeeey bay-huh bit, and the crowd loved it every night. That was a real pleasure for everyone, and also the point in the show, on this late winter evening in Switzerland, when Bill felt something go wrong.

“God, Natty, I don’t feel so good,” said Bill. His head was killing him. He needed to sit down for a second.

A piercing throb in his head. A lightning bolt of pain he could nearly see, and certainly felt, behind his eyes. He might have slowed down for a moment or two, his backing vocal might have dropped out, nobody remembers. Somehow he got to the end of the song.

“Man on the Moon” almost always prefaced “Country Feedback,” at which point Bill switched to bass, so touring guitarist Nathan December was used to seeing the drummer heading his way just after “Man on the Moon” ended. Usually they’d have a moment or two to check in, trade a joke or laugh about something that had gone sideways earlier in the show. But now something was different about Bill. He was pale, and faltering. Usually he’d sling the bass over his shoulder, but now he was swaying on his feet. “God, Natty, I don’t feel so good,” he said. His head was killing him. He needed to sit down for a second.

Bill leaned on the bass amp, December recalls. Then he keeled over. “It was the scariest thing on the planet,” December says. “We had no idea what was wrong.” Peter, seeing Bill go down, dropped his guitar and ran over, as did a roadie or two. Together they pulled Bill back to his feet. He was conscious, sort of standing, but then he fell into Peter’s arms. Peter and December helped him offstage.

They got him to the dressing room and laid him down on a sofa. Bill was conscious and talking. He’d had migraine headaches; those could take him down for a day or two. But this wasn’t that; this was pain like he’d never experienced before. A couple of EMTs came in, took his pulse, peered into his eyes, asked the first question you ask a rock musician who collapses onstage: Was he on something? No? Well, better to not take him to the hospital—they’ll just assume he was overdosing. He had to get out of the hall, though; there was no way he was going back onstage.

The EMTs put him on a stretcher and wheeled him away, taking him back to the hotel. But the crowd was still out there, stomping and cheering, waiting for R.E.M. Would they call it quits or…? No. Someone ran to find Joey Peters, the drummer for Grant Lee Buffalo, who was unwinding in his band’s dressing room. Could he play Bill’s parts? Yes? He grabbed some sticks, sprinted to the stage, the house lights went off, the show went on. The band cut the rest of the set down to the essentials, came off the stage blank-faced and anxious, and were relieved to hear that Bill was resting in his room. It was a bad migraine, but he seemed fine.

Bill wasn’t fine. The pain radiated down to his shoulders. Mari massaged his neck, but then he was nauseated and threw up. He couldn’t sleep; it hurt too much. Mari wondered if he had meningitis. At 6 a.m. she called for an EMT, who came to the room, heard about the neck pain and nausea, put it all together, and called the hospital: Bill had suffered a brain bleed and needed immediate help. They put him back on the gurney, got him down the stairs and back into the ambulance, now with lights and sirens, heading to the hospital, where some kind of fate awaited him.

Rick Diamond//Getty Images

Rick Diamond//Getty Images

Bill Berry of R.E.M. performs at the Omni Coliseum in Atlanta, Georgia, on November 11, 1995.

It could have gone either way. Some people make it and some people don’t. That’s how it is in life, and also in rock ‘n’ roll. It’s all about where you happen to be, what street you walk down, who you happen to meet when you turn the corner.

Bill’s family moved to Macon, got a house in the same neighborhood where Mike Mills lived. Bill and Mike found each other, discovered their mutual love for music, and when they got to Athens they both met Kathleen O’Brien, who just happened to know Peter, who happened to meet Michael at Wuxtry Records, and when they all turned up at the same party, they decided to try playing together. There was no plan, no strategy, just dumb luck that they clicked together so well.

They set out to make music and have as much fun as possible, maybe even make some money, if that’s how it worked out. And it did work out. Club shows, a record, a record deal, onwards and upwards, upwards and upwards and forever upwards, all the way to Lausanne, Switzerland, where the aneurysm in Bill Berry’s brain erupted less than two miles from the hospital, whose staff included some of the world’s best neurosurgeons. Including a doctor who had studied with a neurosurgeon whose recently perfected vascular clip had been developed to treat exactly the sort of burst blood vessel Bill had suffered.

“He’s not going to survive.”

This is what Mari Berry heard when Bill was headed into surgery and she called home to her friend who worked as a nurse. The friend had seen this before. She was so sorry, so very sorry, but when the aneurysm bursts they’re done for, and it was best for Mari to be prepared. But that’s not what Mari had heard from the doctors who were caring for him, so she dismissed her friend’s version and focused on the here and now, in this Swiss hospital, where they seemed so much more optimistic.

They opened his head, found three bleeds, and employed the vascular clips to seal them. Seemingly repaired, Bill was still in blinding pain, but they didn’t want to give him morphine; he needed to be conscious so they could see how his body was responding. A day or two passed and he seemed to be recovering. They were about to send him back to the hotel when a final test, a walk down the hospital hallway, got scary. Bill’s left side went limp; something was wrong.

They wheeled him back into surgery, discovered that his clipped veins were collapsing, then employed another newly developed technique, moving balloons up his carotid artery to expand the vessels until they had healed. Bill was back in his room soon after that, conscious and talking. This time he really was on the mend. He went back to the hotel, and a few days later they moved him to a resort in Evian, where he stayed until he was strong enough to board a jet and fly home to Georgia. There, his bandmates, who flatly refused promoters’ attempts to talk them into performing with a substitute drummer, waited anxiously for their fallen comrade’s return.

Considering how close he came to death, the speed of Bill’s recovery was astounding. Back in Georgia, it took just a couple of weeks for him to get back on the golf course. And even before that he was on the phone to Holt in the office. When could they get back on the road? Bill was ready. Or he would be in just a few weeks. He was already going at his drums, getting his groove back, raring to go. His doctors were fine with it, too. He was as good as new; even better.

They were off the road for exactly six weeks. They lost a couple dozen shows, mostly in Europe and the UK and then a handful of dates in Southern California. But the touring party re-congregated in Oakland for a few days of rehearsals during the first week of May, and on May 15, R.E.M.’s tour, now dubbed Aneurysm ’95, launched its American run at the Shoreline Amphitheatre, just south of San Francisco in Mountain View. Bill, wearing a black baseball cap over his recently opened head, played with all the power and poise he’d had before his fateful visit to Switzerland. Michael made a point of asking after his health a couple of times during the show, prompting the drummer to fake convulsions once and then fall off his stool altogether. It was all in good fun, as was the new image they’d added to the montage that played behind the band during the set: an X-ray of Bill’s head taken in the Swiss hospital, burst aneurysms and all.

And I feel fine.

Excerpted from THE NAME OF THIS BAND IS R.E.M.: A Biography by Peter Ames Carlin. Reprinted by permission of Doubleday, an imprint of The Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2024 by Peter Ames Carlin.

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source link